ANALOG PRACTICE in the DIGITAL CLASSROOM

In the beginning of my photographic journey …

I worked at Tuttle Cameras for over 10-years. While I worked here photography was in an incredibly transitional state – moving from analog to fully incorporating DSLR’s for the very first time. That experience left me feeling very photographically ambidextrous. Over the years I maintained an excellent relationship with Tuttles.

Fast forward to the middle of 2020, as a newly minted MFA with no idea what I c/would do next I turned to what many photographers did during this time: making photographs on film. It was an intuitive turn for me – spirit led even. The slowed pace of the world, mixed with a high level of uncertainty, led me to feeling like the instant intangibility of near perfect digital images wasn’t scratching the itch it once had. I was craving something that felt more tangible. I longed for something I could hold in my hands.

After I ran through my own supply of film at home, I went where I went nearly every time I needed a new roll: Tuttle Cameras. When I arrived I expected the familiar shelves and refrigerator behind the checkout counter to be full of its usual yellow, green, and purple graphically designed boxes. Instead, they the cupboards were bare. No Kodak, no Ilford, no Fujifilm. I deeply was confused. Where had all the film gone?

I found the owner, an old friend at this point, and asked him where it had all gone? With a wide eyed expression he told me they couldn’t keep it in stock. In all is years at Tuttle Cameras he (nor I) had ever seen a day when supply couldn’t match demand. In fact, only months prior to the lockdowns many major film manufacturers were retiring films stocks left and right. And now? They were in high demand, and virtually every film seller in Southern California were out of stock. It took me several weeks to catch an inventory shipment on arrival to get a few rolls in my own hot little hands.

I asked Eric what he made of the surge in demand. He noted that many of the film buyers were younger photographers. He shared there was also a recent increase in print orders. The realization we came to was that younger generations who grew up with screens in their faces and in their hands than our own were facing the COVID-19 crisis were trying to find something that felt real and solid in a moment where life felt anything but certain.

They wanted to hold their something important in their hands.

My goal today is to invite and cultivate a curiosity about the old ways of analog photography. Not because they are old, or for some purist sentimentality. My goal in fostering this curiosity is because from what I’ve seen: the physicality offered in analog photographic practice touches a piece of us that cannot be touched with screens, megapixels (no matter how many), and algorithms alone.

My thesis: making something with your hands can transform who you are as a creative, as a photographer, and as a human being.

The only reason photographs haven’t changed the world yet is because WE DON’T KNOW HOW TO LOOK AT THEM

– Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography

I pivot into the rest of my presentation with this quote because it has been a centralizing concept that is now grounded in my creative and teaching practices.

It frames how I approach my History of Photography class in teaching the visual literacy skills needed to reach photographs – past and present – well and with integrity.

It frames how I approach my creative work, understanding that hand holds to the audience to understanding the work in the context in which it’s presented make it more effective visual communication.

And I would add, that not only do we generally not know how to look at photographs well, we don’t know how to read them in the context of how visual communication has rapidly changed in our society over the past 5, 50, and 150 years.

Imagine a time not so long ago when the constructed images you saw were primarily in newspapers and on billboards.

Imagine a time not so long ago when you saw the scope of your physical existence for the first time.

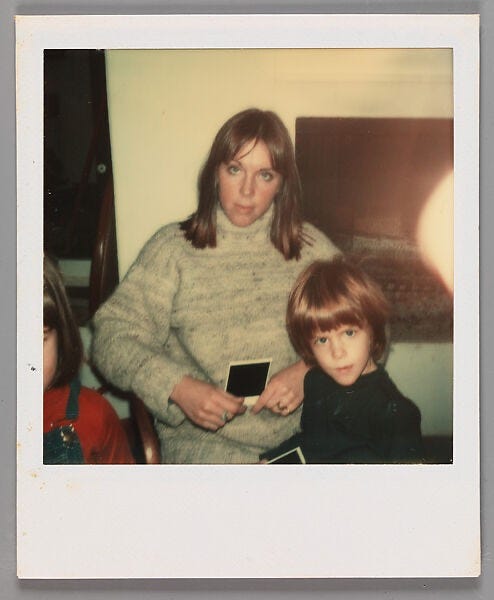

Imagine a time not so long ago when creating family photographs of everyday moments were a rare treasure – often seen as a gift.

Fast forward to today (jump scare!) where photographic images are everywhere … even, as of 2025 some cars are now capable of playing advertisements on your center console.

Consider for a moment: how many images (still or moving) have you seen this morning? This week? This year? The number becomes incalculable.

Do you feel like you’re confidently able to interpret each of those images? I can’t always do that at rapid succession. There’s simply too many.

That doesn’t mean that we aren’t being impacted by them.

The content of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium.

– Marshall McLuhan, The Medium is the Message

From my perspective, in the race to make photography bigger, faster, better, stronger collectively we’ve lost the plot. Or, at least, we’ve forgotten what photographic images do to us.

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan wrote: The content of any medium blinds us to the character of that medium.

Our temptation is to get overwhelmed by the volume of images we see, and by the impressive quality and speed at which they can be made today. However, this reduces or ceases altogether our informed reading of them. Photographs are visual communication – there is something to be read and understood in a photograph – that we are taking in, whether we know it consciously or not.

How’d we get here? Here is the shortest history of early photographic technology (ever):

Daguerreotype: single, positive image (beautiful, laborious, hand crafted items)

Silver Gelatin Sheets: single, reproducible negative (easier to access, but still required level of access to chemicals and specialized equipment)

Celluloid Roll Film: multiples quickly, highly reproducible (highly accessible with many options to export the labor and expertise of creating a photograph – think disposable cameras and 1-hour Fotomats)

Put succinctly photography’s forward trajectory took it from: Single Non-Reproducible Image at Slow Speeds > Many Reproducible Images made Quickly

Now, remember McLuhan’s words: when we are highly impressed with a technology (like photography) we can lose sight of how it’s shaping us as people.

Images are coming at us so fast and so often that our visual literacy skills simply cannot keep up. And the volume of images isn’t slowing down anytime soon. Estimates for 2025 from one agency predict over 2-trillion images for 2025 (I suspect that number may be too low, if we include images generated with AI assistance)

So how do we prepare our students for this reality?

So how do we avoid our descent into a image saturated society where photographs mean nothing? Or where students are not able to distinguish what is real any longer?

How do we empower our students to develop their skill of reading of images, to grow their visual literacy?

How do we re-invite our students to embrace the imperfect messiness of making?

Well, I’m glad you asked! (I have a few thoughts!)

One solution: is we introduce them to analog photographic processes.

A bit of context: CBU-Photography is an incredible digital-based program that prepares our students to enter the industry prepared to embark on their own freelance and corporate photo-based and creative careers.

Let’s talk about one antidote I’ve discovered, through a case study of a class I taught last semester:

In Spring 2025 I taught a special topics course at CBU (with a way too long title) called: Christian Spirituality and the Photographic Process: Exploring the Theology of Image Making.

While we have had students in the past self-initiate their own independent learning with b/w 35mm film (even building out a miniature darkroom in an unused bathroom in campus), there hasn’t been a formal way for students to learn about analog processes prior.

The upper division special topics class – offered exclusively to juniors and senior – served as an opportunity to introduce students to a new way (for most of them) of making photographs through analog and alternative processes.

Students received guided instruction on how to photograph with 120mm film on Holga cameras, and develop their own b/w film. Students were also invited to explore cyanotype process, and creating digital negatives to print with the cyanotype process.

Throughout the semester students also self selected from a provided bibliography of books, such as:

Why Photography Matters (Thompson), Camera Lucida (Bartes), Photography & Belief (Strauss) and others

The readings gave students an opportunity to be reflective on what they learned as they engaged with these new to them types of photo making. Students later reflected that the reading helped give them the language needed to articulate their learning.

The semester culminated in an exhibit at the Riverside Art Museum, just down the road. Their works were curated and installed, with the show opening during an early 2025 Art Walk event.

That reflects both the students’ photographic development and their evolving theology of making, articulated through an advanced spiritual and theoretical framework.

Their works were accompanied by short artist statements about their making from the semester.

While my hopes were high for the impact this class may have on some students. Early in the semester I could see that many of the students were ‘hooked’ you might say from the jump – some even integrating analog making into their senior projects as a result.

What I was not expecting was how it affected them so deeply – or so personally.

I’m going to share now anonymous reflections from a few of their feedback surveys. Please keep in mind that because it was an upper division course, the students you’re hearing from were all juniors and seniors, predominantly photography majors with a few photo minors as well.

There is something deeply personal and physical about film photography — it demands your presence, attention, and intentionality at every stage.

It has taught me about surrender on a spiritual level. The light is beyond your control.

Working with … non-digital processes reminded me to slow down and be intentional. These forms require patience and care, which helped me see photography as more than just a technical skill — [it’s] a personal and emotional practice rooted in who I am.

I’ve come to understand that photography is as much about the journey as it is about the final image.

And no, I didn’t pay these students to say these things! I was blown away by what they were able to articulate about what they learned in this course.

After the semester I spent time reflecting on how something so simple as b/w film process and cyanotype could invoke such profound experiences for these students. My hopes were fulfill – but how did it work?

What I realized was that the tangibility of analog and alternative process photography beckons us back to be a bit more human:

Slow down

Focused attention

Embracing the Imperfect

Experiencing the gift of finite-ness

Analog and alternative process can teach us to see with the heart.

These things were what I studied in seminary! And my undergraduate photography students were learning them through 120mm film.

For our photography students to remain competitive in their fields beyond the classroom, a robust digital curriculum is required. They must become experts in the latest tools and technologies. That is not in question.

However, what might it look like if we add to this excellent curriculum, the human forming super-powers of working with one’s hands in a historically relevant, imperfect process, that teaches us to see (and read images) in a whole new (much needed) way?

To that end I want to conclude with a quote from photographer Gordon Parks:

“I feel it is the heart, not the eye, that should determine the content of the photograph. What the eye sees is its own. What the heart can perceive is a very different matter.” — Gordon Parks

Christine, I am blown away with your insight, knowledge and the clarity of sharing it in this writing. Truly, blown away!

Mom ~ XO